Some answers for frequently asked questions about ADHD. With thanks to ‘Choices and Medication’ for HSE Mental Health Services for the content and research.

1. ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) - read all about it

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder or ADHD is a condition that affects those parts of the brain that control attention, impulses and concentration. The person can not concentrate easily and so has problems at school, play and work.

About 1 in 30 (3.5%) children and youngsters have a full set of ADHD symptoms. In adults, about 1 in 200 (0.5%) have the full set of symptoms, and 1 in 60 have some symptoms (1.8%). This may be lower in adults because their symptoms change and they learn to cope.

You can access the NHS Choices section on ADHD here.

What are the main symptoms of ADHD?

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is also known as hyperactivity or hyperkinetic disorder, although hyperactivity is a symptom of ADHD. Many people think that ADHD has become more common, and that may be true. What is definitely true is that the number of people being diagnosed with ADHD has increased e.g. up by two thirds (66%) from 2000 to 2010, probably due to more people being aware of ADHD (Garfield 2012).

People with ADHD:

- Can be restless, fidgety and overactive

- Chatter all the time and interrupt people

- Are easily distracted and do not finish things

- Cannot concentrate on tasks

- Are impulsive, suddenly doing things without thinking first and have difficulty waiting their turn in games, in conversation or in a queue

- Cannot delay reward or “gratification”, which means that they will choose a smaller reward sooner rather than a larger reward later

- Have problems sleeping, especially getting to sleep and then staying asleep e.g. by 5 years old, only 1 in 200 children without ADHD have more than 3 wakenings during the night whereas 1 in 16 with ADHD have more than 3 wakenings during the night. NB. the average time spent asleep at age 4 years is about 11-12hrs, but this can vary between about 91/2 and 13 hours so remember that all children are different (Blair et al, 2012).

Not surprisingly, this can lead to poor schooling, with the youngsters being thought of as trouble-makers or not very bright. Obviously, if not treated, then these youngsters will not get much out of school, which will have a major effect on the rest of their lives.

Although being like this is common in many children for a while, it can become a problem when this is exaggerated, compared to other children of the same age, and when the behaviour affects the child’s social and school life. The symptoms usually start before 7 years of age. They usually begins to fade in the later teens, or the person learns how to control or manage their symptoms enough to be able to cope.

In people aged over 65 with ADHD, the main problems and symptoms seem to be:

- Always being active

- Being impulsive

- Attention problems

- Mental restlessness

- Low self-esteem

- Overstepping boundaries

- Feeling misunderstood (Michielsen, 2015).

Can adults have ADHD?

Oh yes. As Linda Sheppard (ADHD Suffolk) said “Sufferers don’t just wake up on their 18th birthday feeling fine after years of living with it. ” Sadly, many people (including a few Psychiatrists, GPs and Health Trusts) still don’t seem to think that ADHD exists in adults.

There are 3 types of adults with ADHD:

- People who had ADHD as children who still have symptoms

- People who had ADHD as children who stop the medication and then realise after a few years that they can’t cope and want to go back on medication

- People with a “new” diagnosis. Nearly all of these are people who had ADHD as children but never had a diagnosis. Starting with new symptoms as an adult is probably very rare indeed, and usually means a different cause or diagnosis.

About 1 in 30 adults have major symptoms of ADHD e.g. being overactive, disorganised, often late, choosing busy jobs, poor sleep, often have road accidents and get caught for traffic offences, have poor attention or concentration (the main symptom in 9 of 10 adults), and frequently change jobs even when things are going well. It is easily helped in adults, with the same medications as in younger people, but at higher doses. The usual trouble is getting this diagnosed and treated.

It may also be that adult ADHD is more likely to have been inherited and so have a parent with ADHD. There are over 100 different genes that have been linked with ADHD of which, if you are interested, Chromosome 16 seems to be the main place these genes are found. These genes seem to the ones that control the way brain cells stick together in some areas of the brain that control reward and motivation.

There are, of course, many other possible causes for these symptoms (see next questions) and so a proper diagnosis is needed before any treatment.

The main ways to diagnose ADHD in an adult are:

- Having had the symptoms in childhood

- “Chronicity” – i.e. the symptoms being mostly unchanged since childhood e.g. they haven’t gone away for any length of time. Hyperactivity seems to reduce a bit over the years, but poor attention seems to stay or get worse (Ramos-Quiroga 2006)

- More than 5 symptoms from the lists above

- Symptoms are there all the time e.g. not just at work or at home

- Carelessness and lack of attention to detail

- Continually starting new tasks before finishing old ones

- Changing jobs often, even when they’re going well

- Choosing busy jobs

- Continually losing, or misplacing, things

- Forgetfulness

- Blurting responses, and poor social timing when talking to others

- Irritability and a quick temper

- Taking risks in activities, often with little, or no, regard for personal safety, or the safety of others.

Adults with ADHD may also sometimes take amphetamines (“speed”) illegally. They will say that they take them to feel normal or to help concentrate, rather than to feel high. Adults with ADHD are often not diagnosed and many thus go untreated, ending up with relationship problems, in trouble with the law (see below).

There are some support organisations for adults with ADHD. Our favourite is AADD-UK, “the site for and by adults with ADHD”, which has loads of news, help, advice and support.

The BBC have a fascinating account of a sketch from the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 2018 by Fran Aitken of being given (illegally, of course) methylphenidate in a night club and then realising she had ADHD as it bought her “down to earth”. It’s only a single person’s account but well worth reading as an real person’s experience.

Does anything else have the same symptoms as ADHD?

Because everyone is unique, everyone’s symptoms are different. So, it’s not always clear what the right diagnosis is. Here is a list of some other possible causes for the symptoms of ADHD. This is not meant to be a textbook list, just some ideas. Some of these can be very rare indeed.

- Substance misuse e.g. taking amphetamines, excess alcohol, excess tobacco, or other illicit drugs. People (especially adults) with untreated ADHD are five times more likely to abuse substances, although part of this might be self-medicating e.g. alcohol to help sleep, or amphetamines to help concentration

- Bipolar mood disorder e.g. hypomania or mania. Up to half of people with ADHD can be diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Bipolar symptoms don’t start before 7 years of age (ADHD does), tend to change by getting better and worse and can change without reason (ADHD symptoms are the same almost all the time) and stimulants usually makes bipolar symptoms worse (ADHD improves)

- A Personality Disorder

- Insomnia – which would in turn be caused by something else. Many of the symptoms of ADHD can be caused simply by not enough sleep

- Depression, particularly agitated

- Anxiety or GAD (Generalised Anxiety Disorder)

- Seasonal Affective Disorder e.g. summer highs

- Conduct disorders such as “Antisocial behaviour disorder” or “oppositional defiant disorder” (ODD) – with arrests, detention and aggression. It has been estimated that up to 1 in 10 people in young offender institutes actually have ADHD, about 10 times more common than the general population

- Medical conditions such as overactive thyroid, underactive parathyroid or lead poisoning

- Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) – this is where the person doesn’t sleep well due to breathing problems, and lack of sleep causes lack of attention. Symptoms of OSA include snoring, sleep walking, bed-wetting, and seeming restless in bed

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder – e.g. poor attention, poor memory. People with ADHD are more impulsive and rarely think about their actions afterwards. People with OCD are all too aware of what they are doing, causing them to be hesitant and have difficulty making decisions (Abramovitch 2012).

Adults tend to under-estimate their symptoms of ADHD because they’ve got used to them and feel that they are part of their personality, rather than something that might be treated or helped.

Just to confuse matters further, sometimes people have more than one illness (sometimes called “co-morbidity”). For example, if 1 in 10 people get depressed and 1 in 10 people get anxiety, then just by chance 1 in 10 of the depressed people get anxiety as well. However, if you’re depressed, you’re more likely to be anxious. Co-morbidity means what else the person is more likely to have at the same time. This can make diagnosis more difficult.

- Depression – this is quite common. Up to 1 in 2 people (50%) have both ADHD and depression (Larochette, 2011) and (Michielsen et al, 2012it tends to last into adult life if it starts in childhood)

- Insomnia and sleep disturbances are very common with ADHD

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder – OCD is 4 times more common with ADHD, and ADHD will make OCD symptoms worse (Van Ameringen 2010)

- PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder)

- GAD or anxiety – up to 1 in 4 (23%) may have ADHD and anxiety (Van Ameringen 2010) and (Michielsen et al, 2012 it tends to last into adult life if it starts in childhood)

- Substance misuse e.g. drug dependence or alcohol dependence, which is 3 times more common in ADHD. Remember that adults and adolescents with ADHD may drink alcohol to get to sleep and find they function better with amphetamines

- Antisocial behaviour disorder, ODD (Oppositional Defiant Disorder) or impulse control problems – about 1 in 4 people (25-30%) with ADHD have this, although one can lead to the other (Van Ameringen 2010)

- Bipolar mania or hypomania or bipolar mood disorder – 50% of people with ADHD can also be diagnosed as having Bipolar Mood Disorder. There may be a connection with ADHD, or it could just be a few the same symptoms. It is more likely that about 1 in 10 people (10%) may have both conditions (Karaahmet, 2013).

- Tourette’s syndrome and tics – perhaps up to 1 in 3 [30%] may have tics as well (Nussey, 2013)

- Learning disabilities – as a result of poor schooling caused by the symptoms (about 9 times as common in young people with ADHD). This can include autism (or Autistic Spectrum Disorders)

- Dyslexia

- Epilepsy or seizures – apparently up to 1 in 3 people with epilepsy have ADHD (20339664)

- Getting migraines – having ADHD roughly doubles your chances of getting migraines, especially if you are male (Fasmer, 2011)

- Having an eating disorder, especially if you are an adult female (Fernández-Aranda et al, 2013)

- Schizophrenia – and may also have higher risk of suicidal behaviour (Donev 2011)

- Social anxiety or phobia – although you might actually have less chance of having social phobia (Mörtberg 2012)

- Asthma – having ADHD means you are 2½ times as likely to have asthma (Fasmer 2011)

- Asperger’s syndrome – 1 in 7 (15%) adults may have both (Roy et al, 2013)

What causes ADHD?

Basically, anyone can get ADHD. However, there are some “risk factors” that make it more likely that someone will get ADHD. This is not a complete list but some of the main ones include:

- Being born premature – this is the only risk that has been shown to be definite (Coghill 2010)

- Genetics – having a parent or relatives with ADHD (75% children with ADHD have a parent with it as well), although it is more complicated than this. Genetics may mean that there is a problem with the brain’s “reward system”. When you have something you like, dopamine (a chemical messenger in the brain) will be released in the “reward centre”. Some people may not have enough dopamine (which makes them feel unpleasant and on edge) so always crave anything to release this dopamine as soon as possible

- The mother smoking a lot of nicotine in pregnancy. If the mum smokes 10 or more cigarettes a day during pregnancy the child has 2-3 times the chance of getting ADHD (Lindblad 2010). Smoking after the child has been born more than doubles the risk of getting ADHD. However, the mother smoking both during and after pregnancy means the child has 8 times the chance of getting ADHD (Froehlich 2009)

- Poor sleep or sleep deprivation (just not getting enough) – the less sleep a person has, the worse the ADHD symptoms can get. And the worse the ADHD symptoms the worse the sleep

- Poor housing, not much money, less family support

- Being male

- Sleep apnoea (when you sometimes stop breathing when asleep) – lack of sleep can cause ADHD-like symptoms and sleep apnoea can make it worse and treating this SA can improve symptoms (Youssef 2011)

- Diabetes – ADHD is twice as likely if the mother gets diabetes during pregnancy (Nomura, 2012)

- Having asthma or hay fever (allergic rhinitis) before the age of 4 seems to increase the risk, although this could be partly through lack of sleep (Chen, 2013)

- ADHD is also more likely if you live in an urban or town area than in a rural area (Chen, 2013)

- Not being breast-fed may slightly increase the risk, although it could be that the mum had ADHD too and couldn’t cope (Mimouni-Bloch, 2013).

- Adverse Childhood Experiences don’t cause ADHD BUT make the chances of getting ADHD higher e.g. the mother drinking a lot or using illicit drugs when pregnant; neglect, loss of a parent, serious mental illness in the family; childhood abuse (physical, mental or sexual)

The mum drinking lots of caffeine during pregnancy, or the person having a twin, low birth weight or birth complications do not increase the risk (although some people thought they did). Diet e.g. food additives and allergies, is entirely unproven.

People who abuse drugs get a buzz from that drug increasing the amount of dopamine in the brain. When they do not have the drug, dopamine levels drop and they then crave the drug, to increase their dopamine levels. One way to look at ADHD is that the person always has low amounts of dopamine in the brain. It is almost like the person is in a permanent state of drug withdrawal, but that is the way the brain happened, not because the person has taken drugs. Reward, thrills, excitement, gambling, risk-taking, getting things, amphetamines, cannabis all increase dopamine. As does methylphenidate.

The net result is that it seems that the area of the brain that controls concentration, reward and attention is underactive. This area uses dopamine and noradrenaline as its chemical messengers. It may be that dopamine and noradrenaline are not active enough. Some of the medications for ADHD boost dopamine or noradrenaline and so help boost concentration and attention.

Having said all that, children respond to methylphenidate in the same way no matter what the cause e.g genetic, family etc.

What are the risks of having ADHD?

There are risks from anything and everything, but ADHD has some extra risks. Some of the risks of having untreated ADHD are (for a review see Chang et al, 2019):

- Accidents – people with ADHD are twice as likely to have regular road traffic accidents compared to people of the same age (Ludolph 2009), which is important as road accidents are the number one cause of death in young adults. This is probably due to increased risk-taking and being easily distracted (Merkel, 2013). Also having accidents that cause serious injuries (especially in younger people and males) (Merrill 2009) e.g. burns (Badger 2008)

- Criminal convictions – Twice as likely to be arrested, 5-6 times more likely to be convicted, 15 times more likely to end up in prison than other people of same age, especially for aggression (Mardre 2011), and 12 times more likely to be convicted for violent crimes (Dalsgaard et al, 2013). However, part of this might because someone with ADHD is more likely to get caught. People with ADHD who have treatment are much less likely to commit crimes (Lichtenstein 2012)and 30% less likely to get a criminal conviction

- Poor relationships, sometimes due to “intimate partner violence” (i.e. violence to wife, girlfriend, husband, boyfriend) (Fang 2010)

- Conduct disorder (Fang 2010) or oppositional defiant disorder

- Being bullied: 10 times as likely to be bullied at school, or 4 times more likely to be a bully (Holmberg 2008)

- Stomach pain – twice as likely to have regular stomach pain (Holmberg 2010). About 1 in 20 (5%) have constipation or incontinence. This doesn’t alter whether treated or not treated (McKeown, 2013)

- More likely to change jobs a lot. This is partly from wanting to be busy, and partly from social rejection as it can be more difficult to make friends with someone with ADHD (Jastrowski 2007). 1 in 2 (51%) adults with untreated ADHD had been unable to work in last year, especially if they had lack of attention and other mental health symptoms (Fredriksen and Peleikis, 2016).

- Poorer education – Adults with ADHD may have lower educational achievement levels e.g. not many GCSEs, “A” levels etc. But this is not because of low IQ (Antshel 2009), and is more likely because schooling has not been as effective (Biederman, 2012). Over 1 in 2 (56%) young adults with ADHD have not completed secondary education (Fredriksen and Peleikis, 2016). It is even worse if there is a lot of cannabis smoking and limited parental control (Trampush 2009). Children with ADHD are more likely to have to repeat a year at school

- People with ADHD are also usually financially less well-off, with lower job performance, social isolation and peer rejection. They also tend to become “advocates” for others, especially in older adults, and tend to find ways cope with their attention problems by keeping busy all the time (Brod 2011). They also tend to have a lower self-esteem e.g. having been told they are useless at school, they begin to believe it

- About 8 times more likely to be hooked on tobacco or have more severe nicotine dependence – seems people with ADHD get more reward from nicotine (Groenman, 2013). This is also true for stimulants such as amphetamines. Up to 1 in 2 (45%) people who regularly use or abuse stimulants may have ADHD (Kaye, 2013)

- Excess cannabis use

- Alcohol dependence or dangerous alcohol use (up to 1 in 3 have a major problem), especially if the person also has a conduct disorder (Knop 2009). That addiction or dependence is likely to be more severe and with a worse outcome (Moura, 2013)

- Ending up in prison – a Swedish study showed that up to 40% of long-term prisoners have ADHD, but that only 1 in 15 had ever been diagnosed (Ginsberg 2010), and all had abused substances lifelong. An Australian sample showed 1 in 3 (35%) prisoners had ADHD and 1 in 6 (17%) had the full set of symptoms (Moore, 2013) and a Canadian study showed that 1 in 6 (17%) of new inmates had full ADHD symptoms, 1 in 4 (25%) had sub-threshold symptoms and that those with high levels of ADHD symptoms did much worse when released (Usher et al, 2013)

- Three times as likely to get dementia (Lewy Body Dementia) (Golimstok 2011)

- More likely to have depression and then are 4 times more likely to become bipolar, especially if there is a history of mood disorders in the family (Biederman 2009). What’s more, ADHD symptoms get with increased depression (Simon, 2012)

- Having an adult personality disorder, especially antisocial and paranoid (Miller 2008)

- Having an eating disorder, mainly bulimia nervosa and especially if you are an adult female (Nazar 2008) Someone with ADHD is also slightly more likely to have Binge Eating Disorder (Nazar, 2013)

- Over four times as likely to be overweight (Cortese, 2015) or obese (well, it is in the USA) (Pagoto 2009). This may be due to eating snacks and night eating (Docet, 2012), and/or playing computer games for extended periods of time, whilst snacking. This didn’t used to be a problem but adults with ADHD now have a 70% increased risk of obesity, and there is a 40% increase in children.

- Gambling – someone with ADHD is more likely to gamble and have serious risk-taking gambling (Grall-Bronnec 2011)

- Poor sleep – someone with ADHD will have more problems sleeping, which can lead to depression, drinking too much alcohol, anxiety etc (Accardo 2012)

- The brain taking longer to mature e.g. ADHD slows down the way the brain becomes able to plan for the long-term (i.e. days, weeks, months, years), control emotions, and to be able to delay reward (e.g. if you offered someone without ADHD £5 or €5 now or £/€100 tomorrow, they’d have the £/€100 tomorrow. Someone with ADHD would choose the £/€5 now)

- Having a worse working memory (Alderson, 2013) and generally poor memory in adults, which may be due to poorer learning when younger (Skodzik, 2013)

- Being violent (Gonzalez, 2013)

- Premature ejaculation occurs in over 1 in 3 (42%) men, compared to 1 in 25 (4%) of the general population (4%) (Soydan, 2013)

- Getting diabetes – you have double the chance of having Type 2 diabetes i.e. 1 in 100 (0.9%) compared to 1 in 200 (0.4%). This is not true for Type 1 diabetes (Chen, 2013)

- More likely to have physical health problems e.g. lung disease, heart disease and other long-term problems (Semeijn, 2013)

- Photophobia (e.g. being sensitive to light, needing to wear sunglasses or a peaked hat even in winter) is nearly three times more common (70% vs 28%) in people with ADHD than not (Kooli, 2014)

- Double risk of dying early, especially in girls and women, with accidents the major cause (Dalsgaard, 2015)

- Depression – people with ADHD are 7 times more likely to develop depression but this risk is much reduced by taking methylphenidate, although taking atomoxetine doesn’t seem to reduce the risk (Lee, 2016). Lifetime suicide attempts are 4 times more common (Huang, 2018) if someone has ADHD. Again, taking methylphenidate long-term reduces this risk.

What will happen to my symptoms of ADHD?

We can only guess at what will or will not happen because the following things can have an influence and these are all different for everyone.

- Your age

- Whether you have done well in the past with a treatment

- How bad the symptoms are

- How long you have had the symptoms for

- Any other illnesses you may have at the same time

- The support your family is able to offer and your home-life

- Your job and any stress at work

- Genes – your family history and what genes you might have inherited are often important

- What the words “well”, “better”, “the same” or “worse” mean to you

- What your expectations are – what you expect to be able to do when you are “well”.

- How a treatment works for you, what side effects you have and how they affect your life

- How well you follow your doctor’s or therapist’s advice and instructions.

- Your chances of becoming well again are much lower if you don’t take the medicines prescribed for you regularly and reliably, or you don’t put what you learn from “talking therapies” into practice. You must do your homework!

- With medicines, the dose you actually take, how often you take it and when you take it are all important

What we can’t do is use this to tell an individual person what might happen. Many other things will make the prognosis better or worse.

What will affect the chances of my ADHD improving?

“Prognosis” is the word used for the likely outcome of any condition. There are several things that will help or not help your prognosis or symptoms and the chances of improving. You should try to make the most or build on the good prognosis factors, and try to work on or minimise the poor prognosis factors. That will give you the best chance of doing well.

Factors that may lead to a good outcome (good prognosis):

These are things that give someone a better chance of doing well. Build on these as much as you can.

- Treatment of ADHD symptoms as a child or teenager and continued treatment (no treatment means less schooling or achievement, poor self-esteem, which makes the poor prognosis more likely)

- Being of a higher socioeconomic status and higher IQ, which makes a good chance to have education even more important (Cheung et al, 2015)

- Carrying on with treatment – a Swedish study of over 25,000 people showed that in adults with ADHD, being treating with (and regularly taking) medicines reduced criminality by 32% in men and 41% in women over 3 years (Lichenstein et al, 2012). A review (Chang et al, 2019) showed taking ADHD medicines regularly resulted in:

- Reduced injuries, traumas, road accidents

- Reduced crime

- Reduced thoughts of self-harm

- Reduced substance misuses

- Reduced risk of depression

- Reduced risk of fits or seizures

- Improved education outcomes, especially in higher eduction e.g. sixth form, college, university.

Factors which may lead to a poor outcome (poor prognosis):

These are things that are more likely to give you a worse chance of doing well. Try to reduce these as much as possible.

- Poverty (being poor)

- Over-crowding (lots of people in one house or flat)

- Hostility from others e.g. parents

- Severe symptoms carrying on long-term (Fredriksen, 2014)

- Stress (can make it worse)

- Having a conduct disorder as well

- Stopping treatment

- Having a substance misuse (including alcohol) makes addiction more severe and poorer ADHD outcomes (Moura, 2013)

- For adults, not being treated in childhood

- Becoming demoralised (trying to control the symptoms and e.g. do well at school, but failing and so starting to give up trying)

- Having Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) – having both PTSD and ADHD is bad news (Biederman et el, 2013).

2. ADHD - the options

This website is dedicated to trying to help people get the best from medicines so, for the most part, we’ll focus on medicines. We’ll mention some of the other options, but not in great detail.

Our aim is to try to help people who are taking medicines (or should be) to get the right medicine, the best dose and take it regularly for as long as is right. Any medicines should usually be part of your overall treatment, although some people are quite happy just to stick with drugs or talking treatments. If your medicines are right, then everything else can fall into place. If the medicines are wrong, then they may make the symptoms worse, self-help and help from others will not work as well.

The list here includes most of the main options but does not say what works and doesn’t. Many may be used in combination. Most herbal and alternative therapies have not really been tested in the same rigorous way that medicines have.

For ADHD, there are a number of alternatives, depending on what you would prefer, what might suit you best and how much distress the symptoms are causing you, when and how often.

Main alternatives for ADHD - self-help

Self-help

- Changing diet and avoiding additives (which may help a few people but generally isn’t very helpful in most people)

- Getting enough sleep – making sure bedtime is regular, not late, can make a massive difference to the symptoms. In fact, depriving a youngster of enough sleep can produce the symptoms of ADHD. And, by the way, teenagers are genetically designed to want to go to bed a couple of hours later but also get up a couple of hours later than adults, so they’re not always justbeing lazy or awkward.

- A good bedtime routine is absolutely vital to help someone with ADHD. There should be a clear and regular routine for an hour before bedtime. For children (and adults), you should not watch television, nor use a computer, iPhone or anything else with a screen back-light for an hour before going to bed. Any light like this can stop melatonin being produced by the brain. This then makes it much more difficult to sleep.

- Taking any medicines regularly, reliablyand at the right time

- Putting help from others into practice regularly e.g. attending groups, learning the skills etc

- Speaking to your GP and local mental health team about your symptoms and treatment can also make sure you have the right support. Try and keep to your appointment times if you are able to.

Main alternatives for ADHD - help from others

Help from others

- Psychological management (such as how to manage difficult behaviour, communication, teaching support) can help with problem-solving skills, by coaching, prompting and correcting. Positive Behavioural Support is a way of dealing and helping with behaviour in school. These have nearly all been used with stimulants such as methylphenidate. The therapies are often in groups, 10-12 sessions and last about 45 minutes. They can be very helpful IF the person sticks with the training and puts all the learning into action. But they don’t help if the person doesn’t put the new skills into action. Sometimes these are called “Parenting courses”. This really isn’t the right name. They really should be called something like “behaviour management” courses. They are really about how to help manage the person with ADHD, how to deal with problems and how to get the most out of the medicines.

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) can be of some use (Emilsson 2011) when used with the stimulant medicines and it can help them to be more effective.

- Sensory Integration Therapy can help. It is often carried out by OTs (Occupational Therapists) and helps the person cope with life and events.

- Managing any other problems e.g. mental health problems (such as mood, anxiety), general advice and “life coaching”

- Alternative therapies such as aromatherapy, hypnosis, hypnotherapy, acupuncture, homeopathy homeopathy (click for a review of the 25 studies in mental health by Davidson 2011), (treating like with like) can usually be used in conjunction with (but not relied on to replace) conventional treatments. There is very little evidence for these treatments in ADHD. All of these can be used in conjunction with other therapies. If they work for you then that is fine and we wouldn’t knock them. Click here for a balanced review of complementary and alternative therapies from the Royal College of Psychiatrists (e.g. Ginkgo, Sage, vitamins, other herbal products etc, and some useful links).

- Several studies have shown that Family Therapy and Meditation Therapy are unlikely to help much

Main alternatives for ADHD - medicines

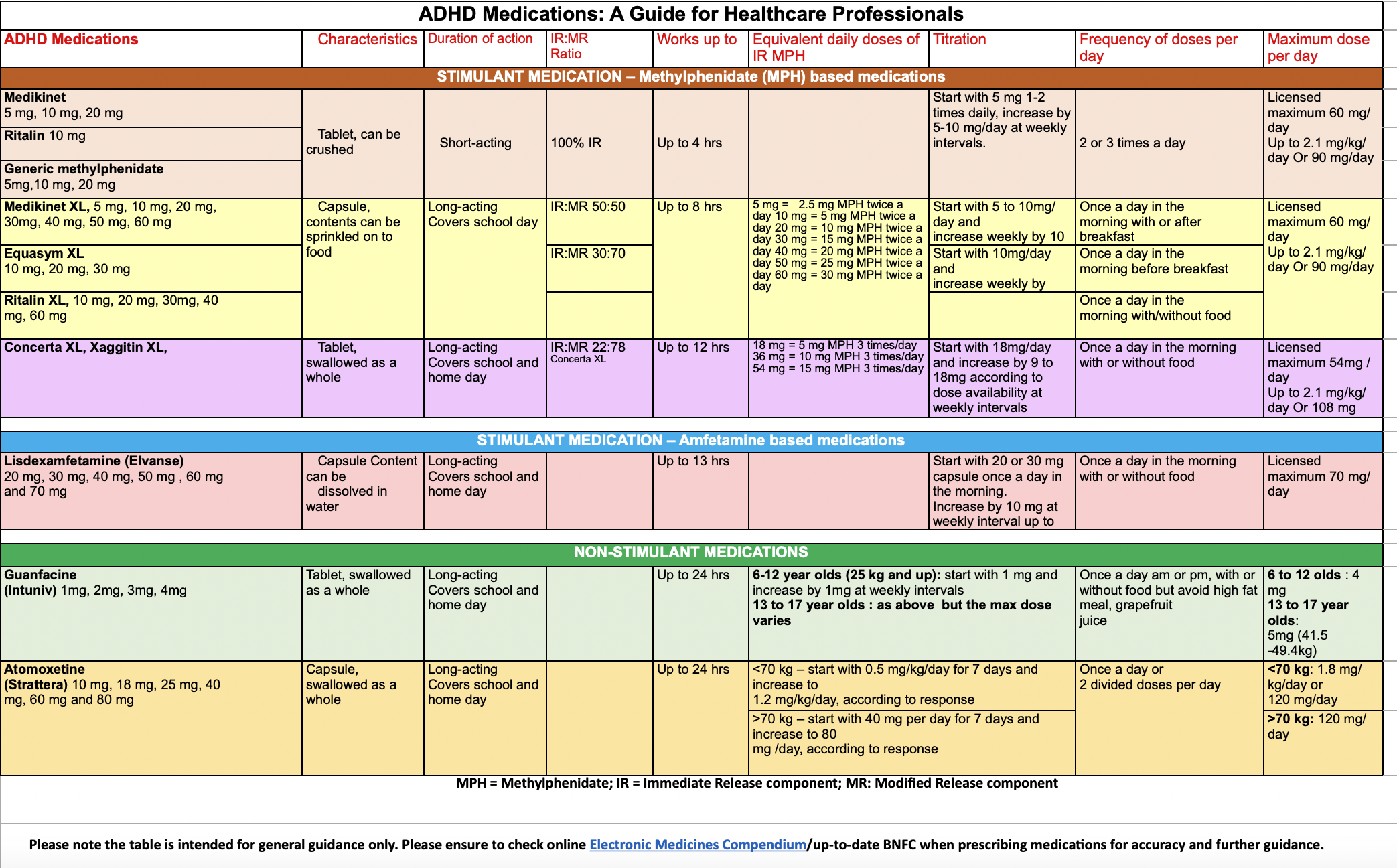

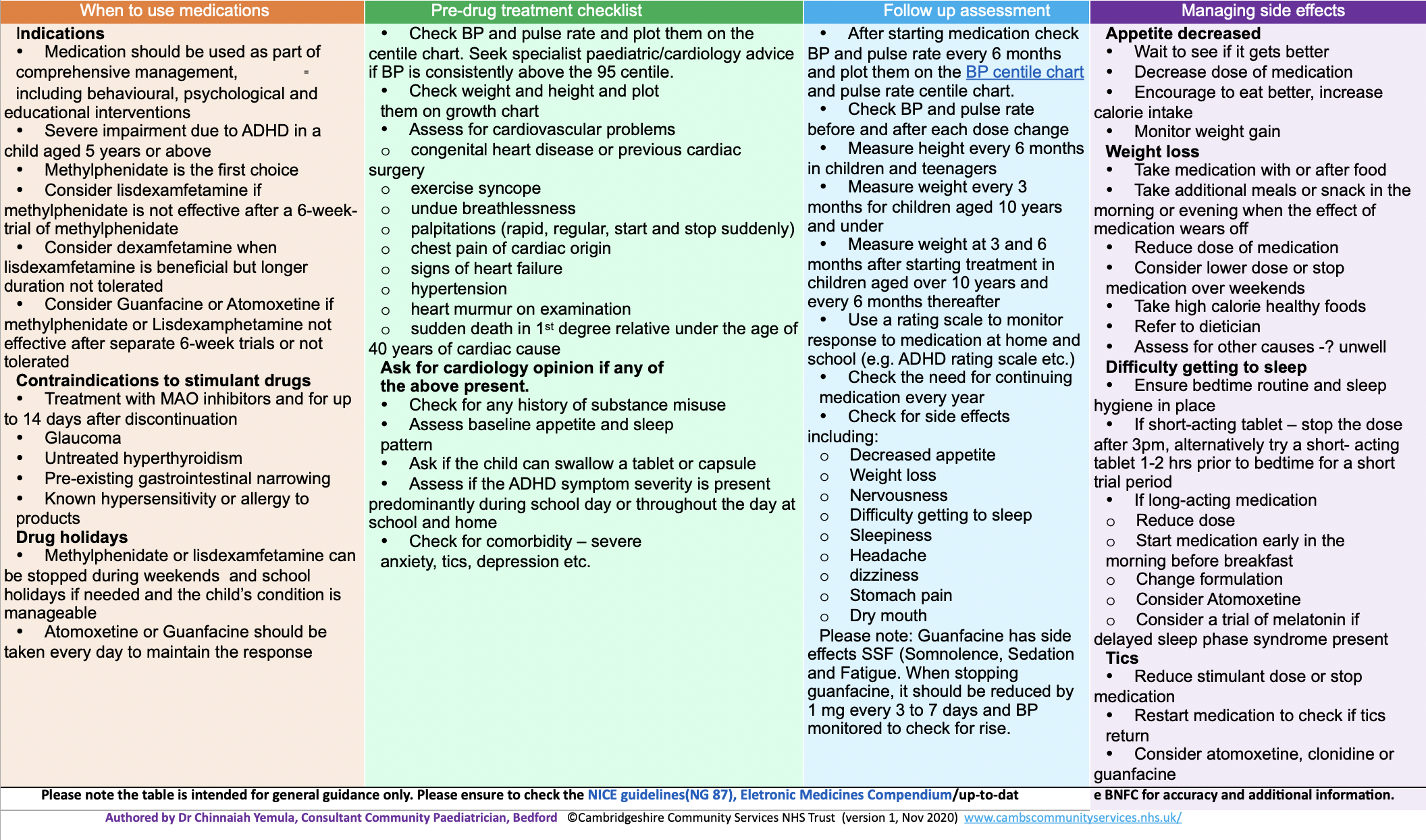

ADHD Medications Guide outlining following medications

Medikinet – Ritalin – Generic methylphenidate – Medikinet XL – Equasym XL – Ritalin XL – Concerta XL, Xaggitin XL – Lisdexamfetamine (Elvanse) – Guanfacine – Atomoxetine

To download the medication table guide here -> ADHD Medication Guide

Please note the table is intended for general guidance only. Please ensure to check the NICE guidelines(NG 87), Eletronic Medicines Compendium/up-to-dat

*** ADHD Ireland is not clinical practice, the information are guidelines. Please, consult with you doctor all medication aspects.

How long will the medicine take to work for ADHD?

Before going onto another medicine, it is worth trying to get the best out of the first one. There is a risk that switching medicines too quickly means you don’t get the best out of one medicine. Then perhaps you start to search for the “magic bullet”, expecting the drugs to work quicker and having less patience. There are of course no “magic bullets”. Most symptoms have started to happen over a few weeks, months or years, not a few days, so it is perhaps unfair to expect them to go over a few days. The symptoms are more likely to go gradually over weeks or months. If side effects are the main problem with a medicine, try to cope with these by e.g. changing times, splitting the dose or manage side effects. See the side effects list for your medicine where there are some ideas. It is always worth having a chat with your GP or mental health team to see if they can suggest something to help with your side effects.

The best thing to do is set out your aims of success of any treatment in advance and be realistic. If you decide to stop, then that’s your decision, but make sure you consider the chances of becoming unwell again (and consequences of that to yourself and the people close to you).

- Methylphenidate, dexamfetamine and lisdexamfetamine – these stimulants usually have a fairly quick effect i.e. some effect within an hour or two of a dose. However, the effect may gradually build, so you should give them about a month or so to fully assess their effect

- Atomoxetine – this is not a stimulant and so doesn’t start to work straight away. Atomoxetine works in about 1 in 2 people within a month, but the effect can gradually build up over 3 months of taking it every day. So, you should give atomoxetine a trial of at least three months (Dickson, 2011). In some people the effect can carry on building for up to 6 months. A few people’s symptoms seem to improve in a few weeks. If you’re switching from methylphenidate you may need to take both together for a few weeks while the atomoxetine kicks in

- Guanfacine – we think it’s about 2-4 weeks after you get to the full dose (which may take at least 4 weeks)

- Melatonin – if there is no effect in 3-4 weeks, it probably isn’t going to help

- Risperidone – usually a calming effect is seen in a couple of weeks.

Is there an easy way to compare the main medicines for ADHD?

Please, click HERE to download a summary chart comparing the main medications for ADHD e.g. names, how they work, doses, how long they take to work, some side effects, how long to take and how to stop.

What are my chances of getting better if I have treatment for ADHD?

Well, here in the C&M bunker, we’ve had a good look at this. We’ve looked at every book in the medical library. We’ve researched information databases as well as medical journals. We’ve even resorted to Google. After this we can reveal that … we don’t really know exactly. It turns out however that this is true of very many illnesses, not just mental illness.

The trouble is, that trials are usually set up to show the maximum effect in a select group of people. And people drop out of the trials for many reasons, meaning the results only apply to people who finished. Again, we have no idea if you are someone like those in that group. We’ve tried to use work done by experts in the field, who have added all the studies together to get an overall result. This is called a meta-analysis.

Whatever you decide to do, make sure you do it. If you decide to take medicines, then take them every day as prescribed, give them a good chance to work, and don’t mess about with them. Medicines will only work if you take them properly as prescribed. If you decide to go for a “talking therapy”, you need to take part fully and put it into practice – do your home work.

A medicine’s chances of working will depend on:

- it being the right medicine for your diagnosis

- you taking the correct dose- very important for ADHD treatments

- you taking the correct dose for long enough

- it not clashing with anything else you are taking.

We’ve tried to do a small table to help compare the medicines.

- By the way, “Improve or respond” usually means your symptoms reducing by at least 50% over the first 8-12 weeks

- All these are best estimates, but each person will be different.

| Treatment | Improve (‘respond’) after 8-12 weeks | Comment |

| Methylphenidate (plain tablets and the once-a-day long-acting ones) | 2 in 3 people (60%; range 25-78%) | Higher response (70%) in children

More variable effect in adults (25-78%) Higher at higher doses and with the once a day doses. |

| Dexamfetamine | 3 in 4 people

(70-80%) |

But this needs to be two or three times a day so is more difficult to remember and take.It doesn’t work if you don’t take it. |

| Lisdexamfetamine | 2 in 3 people (70%; range 60-85%) |

|

| Atomoxetine | 1 in 2 people

(50%; range 40-80%) |

Studies show people carry on improving even after 6 months. |

| Atomoxetine added to methylphenidate in people who haven’t improved on methylphenidate | 0% | |

| Others e.g. bupropion | Up to 1 in 2 (50%) | |

| Placebo (dummy tablets) | 14-50% | Higher in adults |

| Nothing at all | 0% | (Sobanski, 2012) |

In the longer-term, there are some studies looking at what happens if the treatment has helped and you carry on (or not):

1. A big analysis (Shaw, 2012) of 351 studies of long-term outcomes (2yrs or more) in ADHD decided that:

- ADHD treatment improves long-term outcomes (either improving symptoms or stopping them getting worse) compared with untreated ADHD but not usually to normal levels

- The symptoms most likely to improve are:

- Virtually everyone: Driving and obesity – the most responsive symptoms

- Most people: self-esteem (90% improve), social functioning (82%), academic (70%), drug/addiction (65%)

- Some people: Antisocial activity (50%), use of hospital services (50%), occupation (30%) but this may be due to other symptoms e.g. conduct disorder, cumulative effects (e.g. poor education achievement leading to lower grade jobs).

2. There is a definite and measurable improvement in how well people with ADHD function through the day if taking medication compared to adults with ADHD that are not treated (Surman, 2013).

3. Taking medication every day for at least 2-4 years had a much better effect on how well you function than taking it for less than 2yrs (Lensing et al, 2013)

4. A Swedish study of over 25,000 people showed that in adults with ADHD, treating ADHD with medicines reduced criminality by a third (32%) in men and by two fifths (41%) in women over 3 years (Lichenstein et al, 2012)

5. Driving – you will be much safer driving if you take your medication. A large Swedish study (2006-2009) of over 17,000 adults with ADHD showed that, if they took ADHD meds regularly, nearly half of all road accidents involving men with ADHD could be avoided (Chang et al, 2014). For some reason this didn’t apply to women.

If the medicine is working for ADHD, how long will I need to keep taking it?

You should always talk about this to a healthcare professional who knows about medicine treatments for ADHD.

- Methylphenidate, dexamfetamine or lisdexamfetamine – generally, the stimulants should be taken daily (perhaps missing out weekends) for at least several years. Some people say “drug holidays” (i.e. stopping for a week or two every year or so) are a good idea, as they may help work out if the drug is still effective. However, they can make more problems than they solve. They should be done with great care and planning in case things go wrong. And a so-called “drug holiday” is much less fun than it sounds!

- The stimulants are not “BNF listed” or licensed for people starting them after getting to 18 so it can be difficult for GPs to prescribe them for adults, even though their needs may be just as great as younger people. Methylphenidate, lisdexamfetamine and atomoxetine can be prescribed in adults, if the person was treated as a youngster with that medicine. Atomoxetine can also be prescribed for the first time in adults

- Atomoxetine and guanfacine may also be needed for many years, although since they takes a month or so to start working and probably also to wear off, having a week off it may not prove much

- Melatonin usually only needs to be taken for 3-4 weeks to get the person’s sleep pattern right again.However, there are studies that show melatonin still helps even after several years, without any long-term side effects or problems stopping (other than sleeplessness coming back).

How many medicines should I be taking for my symptoms of ADHD?

There are no easy answers to this and it is a very individual choice. Generally one medicine should always be the aim but combinations (often called “polypharmacy”) sometimes help. It is rarely of any use to combine drugs with similar ways of working. Below are some of the combinations that are used with the reasons. This is not a complete list but you might want to talk to your prescriber about any combinations not on this list you may be prescribed.

Usually either a stimulant (e.g. methylphenidate or lisdexamfetamine) or atomoxetine are used, unless you’re switching from one to the other. Sometimes low doses of some antipsychotics such as risperidone can help in combination with a stimulant.

| Main medicine | Second medicine | Reason |

| Methylphenidate, dexamfetamine or lisdexamfetamine | Atomoxetine | While you’re switching from one to the other as atomoxetine takes a few weeks to start working. A very few people might do better with both together. |

| Methylphenidate, dexamfetamine or lisdexamfetamine | Antipsychotic (such as risperidone) | ADHD not doing well just with methylphenidate or where some extra calming is needed. |

| Methylphenidate, dexamfetamine or lisdexamfetamine | Melatonin | To help get sleep more regular. Usually only taken for a month or so (Mohammadi et al, 2012). |

What might happen if I don’t have any treatment for my ADHD?

ADHD seems to be mostly a genetic condition. So, the person has the risk all their life. What happens if not treated will depend on how bad the symptoms are, and how well the person can control them e.g. finding ways to help themselves concentrate. What we can say is that:

- About 1 in 2 (50%) teenagers seen at ADHD clinics will still have symptoms of ADHD as adults

- About 1 in 3 (37%) of youngsters with ADHD do not get secondary or high school certificates

- About 1 in 2 (50%) never take any exams

- Adults with ADHD have less chance of getting a University degree. The rate is about 20% (a fifth) of what you’d expect

- Adults with ADHD who are not treated are more likely to:

- Be unemployed

- Have road accidents (because they lose concentration; For more details about ADHD and driving in UK go to www.gov.uk/adhd-and-driving)

- Get caught for crimes (we have heard that 1 in 10 people in prison have ADHD)

- Have sleep problems

- Abuse drugs (sometimes to help sleep, sometimes to help concentration) – and taking drugs such as methylphenidate reduces the risk of going back to abusing drugs once someone has got off them (Konstenius, 2013)

- Have relationship problems (not managing to keep a relationship going).

You also need to see the “What are the risks of having ADHD?” above for all the risks.

3. ADHD - decision making

In mental health there is rarely a clear best choice. No treatments are universally effective and all have different risks so most choices involve a trade-off between the effects and side effects of the many treatments. We still don’t know why particular treatments work for some people but not others and only partly in others. So, there has to be a bit of guesswork but the more you know the better the guess is likely to be.

Shared decision making:

The aim of shared decision making is to come up with a plan that is agreeable to both parties, likely to be effective (i.e. there is evidence that it will work) and practical. In most cases some shared decision-making in mental health should be possible. In fact, treatments may actually be more effective if you’re involved with the decisions (see Drake et al, 2009).

Healthcare professionals should know about:

- The problems

- The possible treatments

- What has worked for other people like yourself

- The potential benefits and risks of each of them for you.

You will know about your own:

- Values

- Goals

- Support and preferences.

You can really only make shared decisions when both you and your healthcare professional know enough about the options and are up-to-date. To help this is the main reason behind putting together this website and making it freely available.

Appointments:

- A big problem is forgetting what questions to ask and finding it difficult to express yourself so write your questions down in advance

- Read up as much as you feel comfortable with in advance. Then your time with a clinician can be discussing the risks and benefits for you rather than general education.

- Prepare before your next meeting and be clear about your options

- Take someone with you if you want

All this takes time and the health services may not always be set up for this with standard appointment times, so best to be prepared by reading what you can first. A few doctors may not be quite ready for shared decision making. Some may have concerns about whether you are well enough safe decision making and of their legal responsibility to care for you.

General information:

- You need to make a decision, even if it is to do nothing (“watchful waiting”) at the moment (unless you are under a MHA section)

- You have the opportunity to find out about the treatments so, even if you then let someone else make a decision, at least you know nothing is being hidden from you

- Ask your doctor and other healthcare professional for advice – they should have more knowledge about the options

- Don’t be misled by reports you may see in the newspapers as they almost always don’t give the full story

- Don’t rule anything in or out just on principle

- Your decisions can change with time, based on e.g. symptoms, experience, severity, and the outcome of other treatments

- It is best not to make big decisions when you are very unwell.

- Remember: The main thing that matters is to help you to get on with your life and not to suffer the symptoms.

Should I be worried about taking medicines for ADHD? Are talking therapies better?

You should think carefully about taking any chemical that affects your body, including your brain. Even too much caffeine found in tea and coffee can affect your thinking.

There is concern in many countries about taking “stimulants”, especially in children and also that methylphenidate may possibly used a bit too often. This is a natural fear. There are, however, no known major long-term side effects from these stimulants. On the other hand, there many people who do NOT get treatment for ADHD who would benefit from it. ADHD can be a serious handicap, affecting schooling, social skills and jobs, which DO have long-term adverse effects.

Many people have the view that methylphenidate (often called Ritalin in this argument) is being used too often and that children without ADHD are being prescribed methylphenidate. It is worth saying here that when ADHD is diagnosed, it should be done using a proper rating scale and using the guidelines from NICE or other world-wide agreed lists (e.g. DSM-5). This should help make sure ADHD treatments are not being used randomly or too easily.

Talking therapies can help reduce some of the hyperactivity symptoms, and possibly also help anxiety, low mood and low self-esteem. All the Talking Therapy studies have been carried out in people also taking methylphenidate and similar medicines. This is fairly sensible as you need some concentration to learn the ideas. The effects of talking therapies tend to wear off over a year or so, so a “top-up” or refresher may be needed. Medicines wear off in a few hours of course. And of course if the talking can help the person know what makes their symptoms worse they can do something about it. Coaching can also help a lot by helping the person learn how to deal with a brain that’s always on the go and look-out for something new and exciting.

For an appeal for everyone to have a sense of balance about medicines and talking therapies please click here for our take on it.

Are there any guidelines I can look at for the treatment of ADHD?

If you want to read up a bit more on the best treatments, there are many guidelines that you can look at. Probably the most important of these for England and Wales are those produced by NICE (the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence). NICE is an independent body that is asked to produce advice about preventing and treating illnesses and promoting good health. Scotland has a similar group called SIGN.

Each set of NICE Guidelines is usually written by an independent and carefully chosen group of specialists and experts (including service users and carers). They review the available evidence and base their guidelines on this.

There are two main types of NICE guidance:

- Technology appraisals. These look at an “intervention” (i.e. a medicine, a surgical operation etc) and decide if they think the evidence is good enough to make this intervention a standard and/or if it is cost-effective compared to other treatments

- Clinical guidelines. These look at a particular condition (e.g. hypertension, lung cancer, depression, Parkinson’s disease, bipolar disorder etc) and give guidelines covering medicines, talking treatments, support from other professionals and other services.

There are other types of guidance e.g. Public health guidance, Social care guidelines, quality standards and so on.

The concept of NICE guidance is well-intentioned and to give sound guidance. It has to be added that the mental health guidance can sometimes be controversial and their conclusions are not always accepted by everyone. They are, however, only ‘guidance’, so are not rigid rules as to what should happen. They are ‘guidelines’ not ‘tramlines’.

When NICE issues a guideline, it produces a series, and all of these are available on the NICE website. These include:

- Full guideline (very long and detailed, often several hundred pages, for anorak healthcare professionals only)

- Official guideline (usually 10-30 pages, the summary version for healthcare professionals)

- Information for the public (user-friendly summary for service users, carers and the general public).

These should then be reviewed, usually about 4-5 years, or sooner if more information becomes available.

As a general rule, you should start with treatments recommended by NICE as these are the treatments with most evidence that they work. However, if these do not help you, it may be useful to try other treatments.

- NICE (click here for the 2018 ADHD guidelines) including clonidine for treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and young people and using melatonin to treat sleep disorders in children and young people with ADHD

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines for the Management of ADHD in children and young adults (October 2009)

There are plenty of other guidelines and so-called “consensus statements” (where a group of experts and specialists pool their ideas, based on their own experiences as well as what the published papers say, rather than just what the published studies say). These will have been produced for healthcare professionals by such bodies as BAP (British Association for Psychopharmacology).

Where can I find out more information about ADHD?

The resources below provide more information about Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Please note that this is not an exhaustive list. We welcome your feedback on resources that you think should be listed here.

- Mental Health Ireland has a great links page on this extensive site

- Your Mental Health Ireland, with a young person’s page as well

- ADHD and You, a website from Shire, who make Equasym XL, with some handy stuff on ADHD for parents/carers, teachers, professionals and, of course, people with ADHD

- ADDISS, The National Attention Deficit Disorder Information and Support Service are a great ADHD organisation, led by Andrea Bilbow

- The British Association for Psychopharmacology has a BAP public area, which has loads of interesting articles, some mentioning ADHD. There is a report of the Cambridge Science Festival March 2013 Event – “Focusing ADHD” – you can click here for the readable summary

- The Big White Wall is a 16+ safe, anonymous web-based service for people experiencing emotional or psychological distress provided entirely online. Professionally staffed 24/7 it offers a wide range of services for improving mental wellbeing including tests, peer support, individual and group therapies, articles, tips and creative self expression. Simply click on the link to learn more, or to join for £2 a week.